(13) Against Simplified Constructs

a call for technology and design to consider more varied embodied experiences

These past two months, I traveled to three different cities for work, home, and vacation. At NYC MoMA, I came across a collection titled “Body Construct.” Revisiting the MoMA website after my trip, I learned that the collection explored two polarizing yet complementary design practices:

“[on] the invention of narrowly defined 'average’ human figures intended to support universally applicable designs; and an urge to challenge the belief that such simplified constructs could encompass the full range of bodily variation and embodied experience.”

This description deeply resonated with me because my written and artistic practice often transpire from a constant desire and effort to become acquainted with my body and its embodied experience. I say “its” because sometimes my body feels like a temporary settlement, a tenuous habitat that requires constant upkeep and discipline of conscious listening to be a resident. It has taken a while for me to reach a place of peace that my bodily residency is contingent on the fact that I will perhaps never fully know my body, and that’s okay. But this is all old news to some of you already.

So yes, bodies varied, designs universal. While the collection showcased pieces dating back to the 1950s—1970s, the theme felt relevant to present day. It reminded me of the time Khang and I were at the Stonestown mall parking lot and we saw a digital ad of a TikTok tutorial on how to bake chocolate peanut butter brownies. The screen was long and vertical, shaped like a phone, but blown up in size to be about six feet high. Khang said, “it’s so weird how ads [and their screen counterparts] are now designed in a way that mimics cell phones and vertical scrolls.” The universal UI of phones and platforms was infiltrating the day to day to physically present itself as a looming sculpture in a mall parking lot. These vertical digital billboards were not new, but perhaps felt more dystopian than usual to see the buzzing screen of the blown up ad reel on repeat next to a row of charging EVs, mostly Teslas, in front of a beautiful sunset.

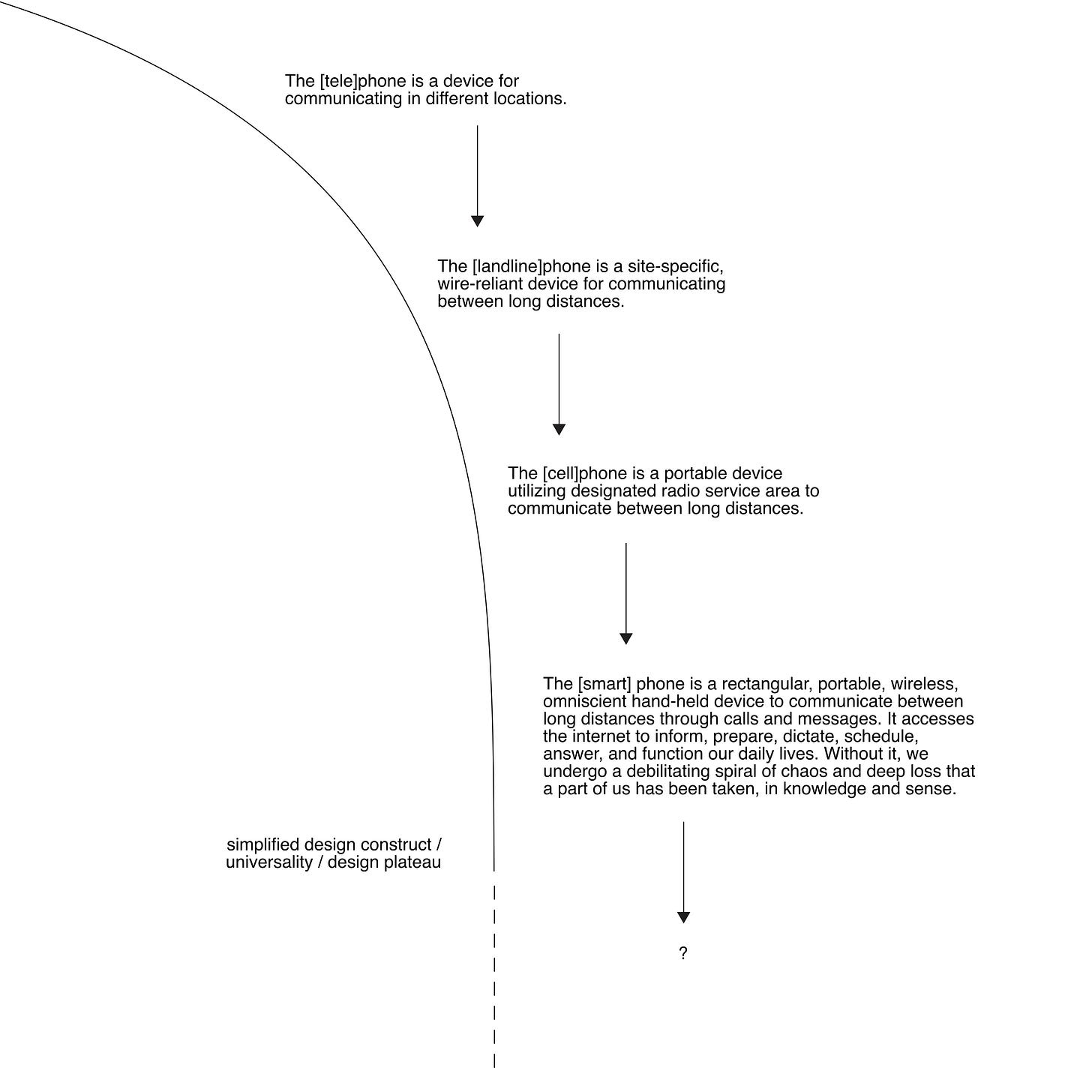

In technology, simplified constructs can be seen as pre-determined configurations of devices, inevitably driving any design exploration to exist within this constraint. For example, we have settled with the presentation of the phone as a rectangular, vertical screen. Whether it be by comfort, by marketing, by the ease of handling, by the rationale that this is really the only logical way to make a phone, or by the initial design that set the construct, there haven’t been many efforts to redesign the phone. Groundbreaking explorations in design now happen within the device: platforms, apps, websites, and everything the rectangular block can interface.

Although I do not own a Samsung phone and will find it difficult to switch anytime soon, I find Samsung’s exploration in technology commendable. Samsung’s foldable phones challenged industry standards and distorted the construct of how a hand-held device should be designed and engaged with. This isn’t a comment on which design is superior or which makes more sense. But rather, the wider the choices, the greater the authority users have in making a more selective, personalized decision in how they wish to engage with the technology. Whether it be a compact sized Z flip, a book-like Z fold, or a rectangular iPhone, a broad range of choices makes room to account for more bodily variation.

I had a silly thought exercise: what if we weren’t bipedal creatures reliant on our hands? What if we had to scroll with our toes or our knees? What if our hands were wide instead of long? what if we didn’t have hands at all? What would these phones look like? Would this call for a wider consideration and exploration of design and accessibility where our daily devices can “encompass the full range of bodily variation?” Or would all things, with time and evolution, reach a design plateau? Are simplified constructs and design universality inevitable with advanced progress? I am unsure.

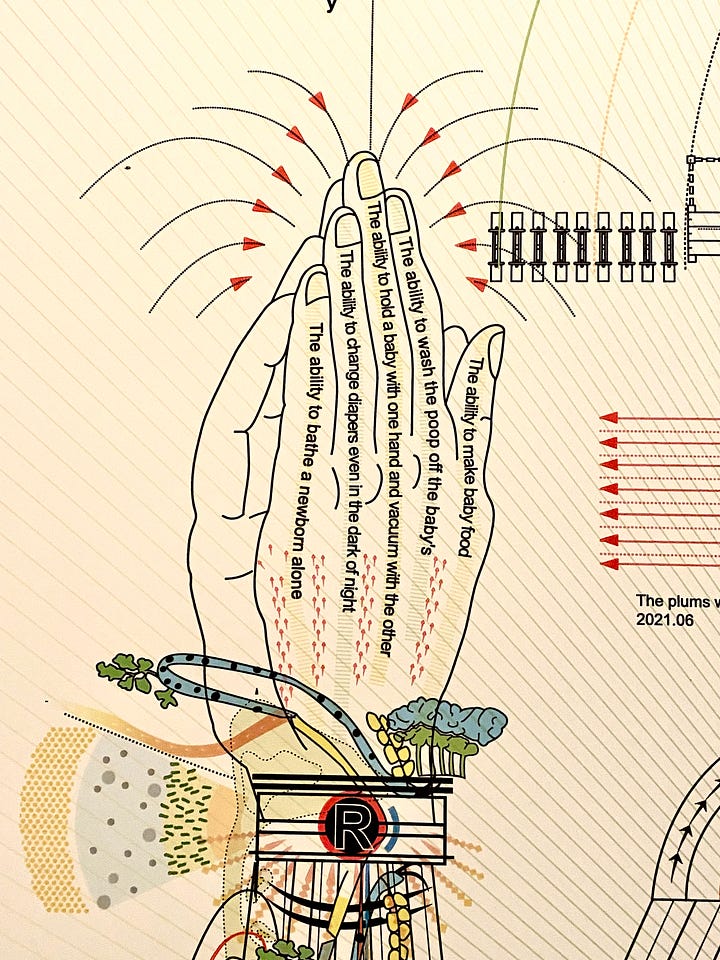

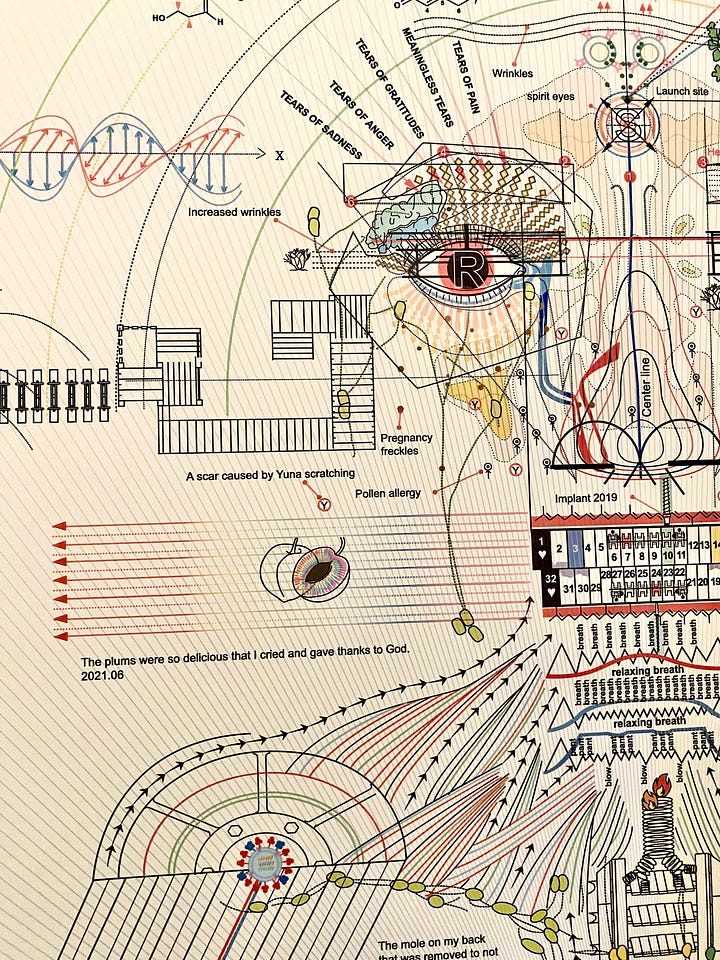

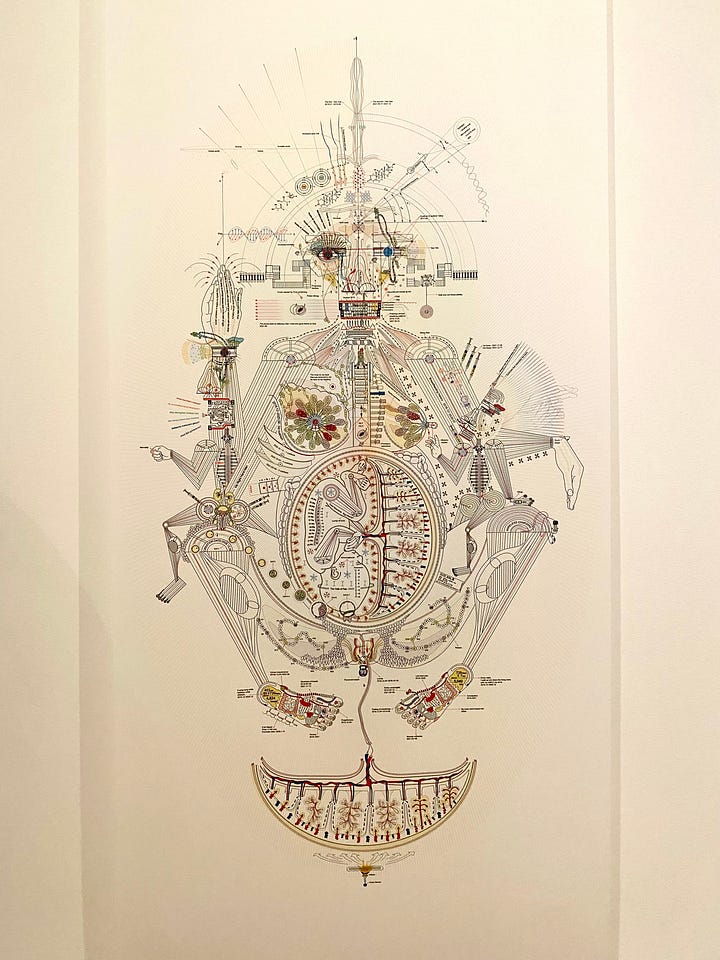

There was a piece positioned at the entrance of the Body Construct collection that left quite an impression. Titled “Self-Portrait_Rachaph" (라하프) by a Korean Artist Minjeong An, was a banner sized digital print. What looked like a technical anatomical diagram at first glance was actually an archival retelling of the artist’s body. Her lower abdomen documented the entire cycle of her pregnancy from fertilization to birth. Her back recounted, “the mole on my back that was removed to be not seen at my wedding.” Each finger held a special skill such as “the ability to bathe a newborn alone.” Above her eyes were five different modes of tears that arose from pain, anger, sadness, gratitude, and without meaning.

I was so taken by the expansive logic in her art coupled with personal, lived accounts archived by and on her body. Her anatomy was composed of nuts and bolts, cells and sensors, glands and nerves, a mix of robotics and biology. The details of each label — whimsical, historical, and nostalgic — were experiences only the author could recount and claim as her own. Technology could never capture this level of personal whimsy, the knowing and embodying that simply comes from living, that is. But we always try to imbue what we can online to make meaning.

An’s diagrammatic interpretation of her body and lived experiences made me recount my own: the double eyelid on my right eye that suddenly appeared in my senior year of college; the mole next to my belly button that has accompanied me since birth; the birthmark on my left hip; the calloused middle finger that cushions my writing. And in many ways, I have seen my relationship to technology change as I moved through the years. In particular, the way I grip my phone has changed. What used to be a precarious rocking single hand hold has now resorted to a double handed grip or a surface to prevent wrist arthritis.

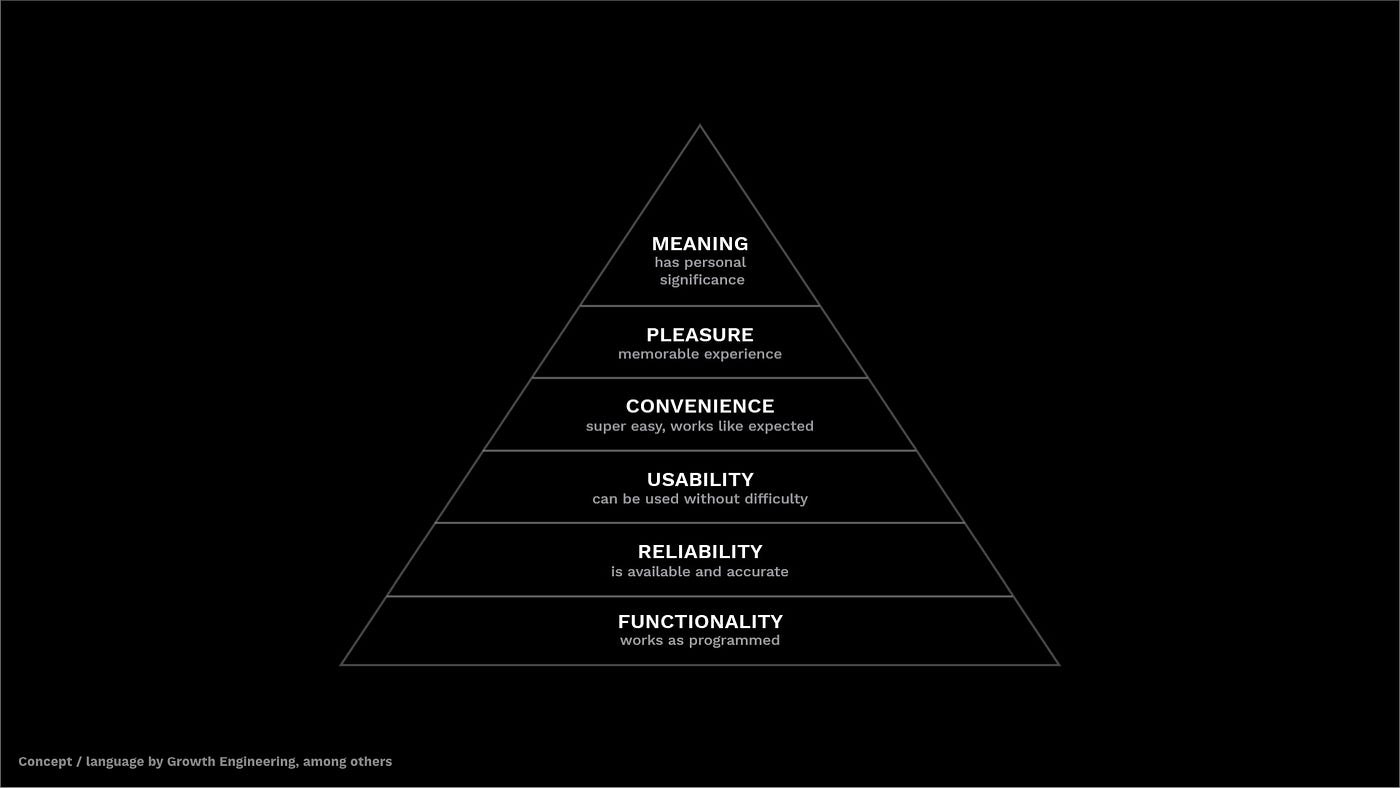

On Medium, I found a diagram akin to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs outlining what users value in an interface. The author shares,

“The plateau we sense, the sameness we see — this level of design climbs pretty high up the pyramid. Many of these interfaces highly usable. BUT — few of them are meaningful, or pleasurable in any deep way.”

It seems that we have cracked the formula for making functional, reliable, usable, and convenient things, but reaching the top of the pyramid is still an on-going effort. I feel that we have somewhat plateaued at the edge of pleasure — cheap, fast pleasure — that are difficult to categorize as truly memorable or a step further, meaningful.

Technological advancements and their design counterparts are no longer looking for “the solution.” They have surpassed difficult mechanisms to now look towards efficiency, lightness, aesthetics, productivity, and personalization. Greater compression, faster builds, more remote access. But I wonder if there has been a a consideration for a shift in the “average” human as we continue to coexist with these evolving technologies. I wonder how technology would evolve if we actually did consider the full range of bodily experience, big and small. Maybe these considerations are inefficient, unproductive, and backwards. But perhaps today’s most cutting edge technology does not exactly entice or serve the average person anymore.

In San Francisco, I see silly billboards about GPU’s and CPU’s, shipping (not online deliveries), and an array of unintelligible symbols and letters. Coming to understand some of these messages makes me feel included in an inside joke whispered through the city. These signs remind me that people build tools not just for the average person but also for those building for the average person. Their world is niche, immersed, odd, and sometimes too parochial for people on the outside to understand. But sometimes this feeling is mutual for those on the inside too.

Here, I have met a wide range of individuals. Those passionate with a fervent belief in big tech, feverishly dreaming and building to live by and for the technology that is their savior. Some, a bit more jaded or well-balanced, utilize technology as a means to an end to support their livelihood and set necessary boundaries. Then there are others who are free, not bound by the glitzy motion of the city. They create liberally and search openly to forge new paths outside of what is simply handed to us. My constant struggle to challenge and deepen my craft is an effort to walk towards this practice, as this is where I would like to be.

As we continue to create towards a place of sustained liberation together,

— Eileen

Other musings:

🟨 The Internet Phone Book by Kristoffer Tjalve and Elliott Cost is officially live for you to dial a poetic web. They are going on various book tours this year and might be coming to a city near you! Find my piece, A History of My Websites, originally published on Schema Acquisition featured as a contributing essay.

🍬 Pink Trombone is a silly website that makes lingual sounds. I have been playing on this website nonstop.

🧶 Antique Pattern Library catalogues useable patterns for knitting, crochet, and various other needlework with designs dating back to the 1700’s.

📚 Continuing Studies by Taeyoon Choi is an are.na board that houses free, cheap, reasonable MFA/PhD/non-accredited learning programs for artists/researchers.

✍ Say Translation is Art by Sawako Nakaysau. Highly recommend.